This week in high school comics class: working on outlining and structuring our minicomic stories. The structure is there to support them when they’re stuck and for them to rebel against when they’re not. P1: Introductions – We learn about

Read More

Tag: storytelling

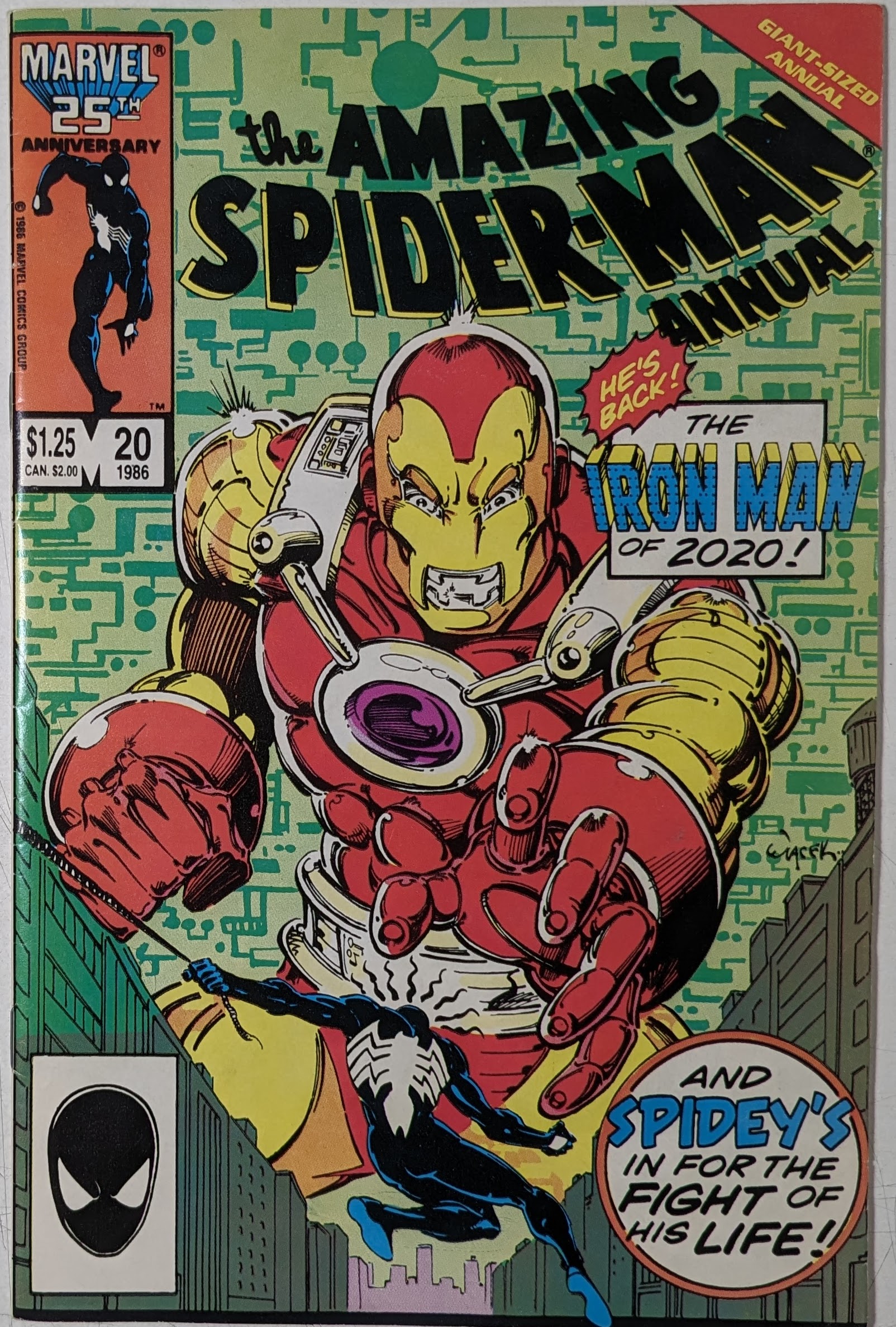

❤️Spidey Beat Up Iron Man 2020 & That’s Why I Love Him❤️

I’m not sure when I got The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #20. I think it might have been Christmas of 1990. My parents, resigned to the fact that I was hopelessly in love with comic books (especially Spider-Man), got me a

Read More

My Kid Could Do That!

…it doesn’t have to be by a well-known artist. A child can do an archetype, maybe probably does more type of [archetypal] images than artists do. They spontaneously arise. Thomas Singer, Jungian Analyst I was arrested by this bit on

Read More

Thunder Punch Daily 143 – Surprised by Style

Today I share some thoughts on how a simple nudge from Kim Holm faced me with an inner demon that I suspect comes out of my history with mainstream comics. I don’t land on an answer to the issue, but

Read More

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Thunder Punch Daily 132 – Knitting Scenes Together

I was asked an interesting question in my Comic Book Academy class about how to figure out an order or sequence of scenes for a comics story. Today I share the answer I gave in class. Mentioned in this episode:

Read More

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Thunder Punch Daily 131 – Other Lives

Today I give a sort of book review of a comic I finished recently–Peter Bagge’s excellent Other Lives, published by DC’s Vertigo imprint. I break it down by plot and theme, but as you might have guessed, I also talk

Read More

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Thunder Punch Daily 117 – The Art of Conversation

Today I share an exercise I’ve used in my classrooms to teach some vital comics storytelling skills. By drawing a conversation sequence, we explore moment choices, scenery, emotional context, acting moments, and best of all, word balloon placement! Also mentioned

Read More

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Thunder Punch Daily 113 – Shape, Size, & Line

Continuing my series of TPDs recorded on my drive to Grant, Michigan for the Kids Read Comics Super Fun Tour, I ruminate on some classroom interactions I’ve been having lately that remind me of some of the basic concepts of

Read More

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Thunder Punch Daily 107 – Aboutness

Today I revisit some thoughts on writing, and a go-to technique I use to write stories for clients and for myself: starting with a takeaway, or finding the story’s “aboutness”. It’s a slippery topic, and I’d love to hear from

Read More

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Thunder Punch Daily 98 – One Week Later Observations

Sharing a few thoughts on what I learned and what I fought against in making a mini-comic in a week! Surprises, sadness, and finding my courage to press on. By the way, the mini-comic is complete! You can read it

Read More

Podcast: Play in new window | Download